|

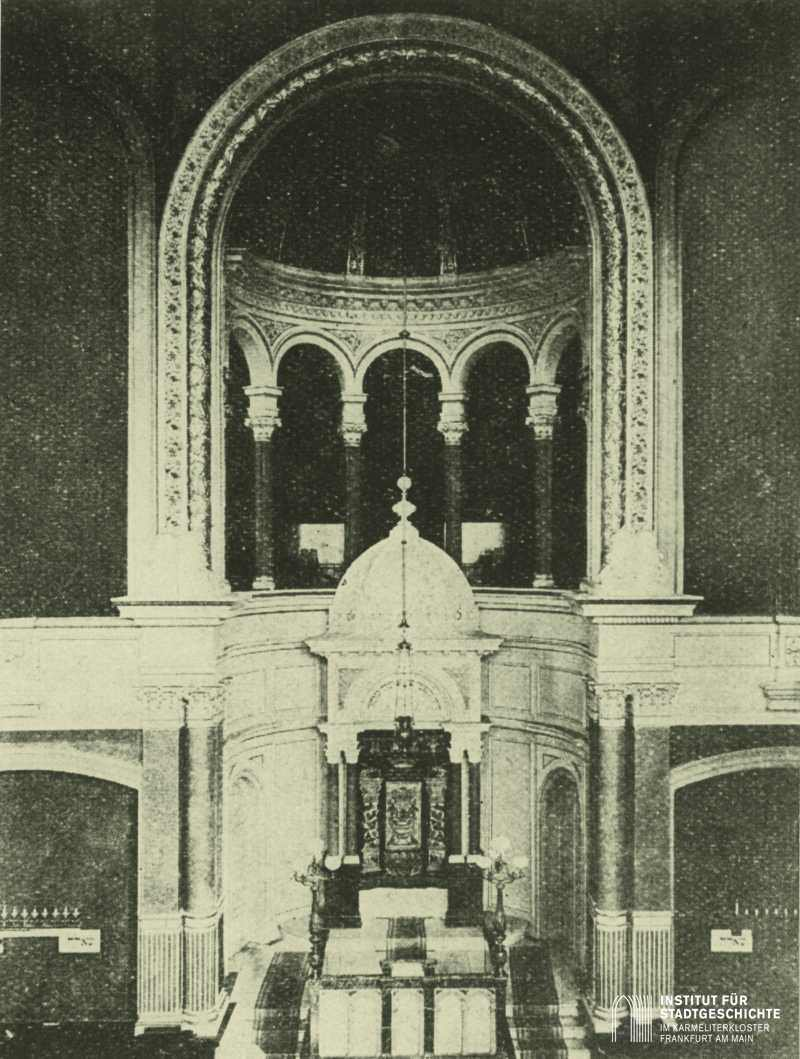

| Boerneplatz Synagogue, Frankfurt am Main, prior to its destruction during Kristallnacht |

“There wasn’t a minyan, but the shul was full of

angels.” My rabbi, Rabbi Meier Schimmel,

told me this is what either his father or one of their rabbis said when, after

the Nazis came to power, fewer and fewer people ventured out to their synagogue

in Frankfurt. It is an instructive and

powerful response to what could have been a profound moment of loneliness. One so strong that the impression it made in

the mind of the young man who heard it lasted the sixty years until he told me

and then more than another twenty for me to tell you.

Loneliness is a terrible plague, and just because the Jews in

1930’s Germany would come to know far more terrible catastrophes does not

lessen what it is to be bereft of companionship.

Loneliness is addressed by community, but as we all learned

eight decades ago, not community in the way you might think.

Finally, loneliness might be the result of immoral, inhumane,

even evil deeds, but, in itself, it is none of these things. A community that recognizes this distinction

is a true one for its members.

--

Loneliness is a Big Problem

In May, Vivek Murthy, the Surgeon General, released a report

on the epidemic of loneliness confronting American life. Made worse by the Pandemic, Americans since

1976 have indicated growing rates of loneliness and isolation. Being “disconnected” from family and friends

and suffering prolonged bouts of loneliness have health impacts as serious as

being obese or being a heavy smoker.

Profoundly isolated people are angrier, sicker, more depressed, and more

likely to commit suicide.

Various factors are mentioned as compounding this very

serious threat. The emphasis Americans

put on material wealth that pushes us all to see work as the key indicator of

success. The inability to “go home” at

the end of a hard day’s work because phones and emails and computers and more

go home with us - only made worse when home became the office – it is no

surprise that we have a real issue with isolation and loneliness.

The study also points out that, “from 2003 to 2020 young

people’s time spent physically in the presence of their friends declined by

70%. While I’m sure this is true, this

is one of the only alarming revelations about which I am a bit suspect

regarding the conclusions they are drawing.

In the 70s, 80s and 90s, the worry was we were sitting too close to the

TV for too long watching one of the four channels available. Then it was that we were spending too much

time engrossed in the alternate universe which was a Pac-Man arcade or video

game. Adults are always going to be

worried that the phonograph or talking pictures or the Tic-Tac will irrevocably

corrupt the next generation. That is not

to say there isn’t anything to worry about, but the sky doesn’t need to be

falling for something to be really bad.

Finally, the alarm is not limited to just those who work and

those of the up-and-coming generation. The

tragedy among so many of grandparents and other older Americans being isolated

from family, sometimes in the most pressing of situations during the Pandemic

was yet another extreme example of growing trends towards being alone as we enter

the later years of our lives.

--

It Takes a Community

Not surprisingly, numerous responses have been penned to the

Surgeon General’s report. Rabbis, ministers, researchers, and even former

Secretaries of State have all responded.

In her Atlantic piece, Secretary Clinton, as many others do,

points to the erosion of the various institutions that in the past brought

people together and kept them connected, “attending religious services, joining

unions, clubs, civic organizations – even participating in local bowling

leagues-were disappearing.” Clinton

writes with a focus on political polarization in mind and so also notes that the

report says, “diverse, robust, social networks make the American dream possible…

without them, it…has significantly reduced economic mobility in America.”

What religious organizations do to counteract the sickness of

loneliness is further discussed in an article from the Boston Globe by

Rabbi Elan Babchuk. He notes the study doesn’t

sufficiently acknowledge that faith communities can be part of the solution

instead of “part of a list of divisive topics that cause polarization between

individuals and communities.”

When Rabbi Babchuk elaborates on the good religious groups

can offer, his examples involve a Baptist Church organization that worked at

combatting obesity, starting by banning fried chicken at church events and

installing a track around the church grounds – or another religious group that

helped get vaccinations to people during the Pandemic (as the Galinkin Family

helped us do here at NSJC). To these he

adds the benefits that can come from gathering inside houses of worship,

too.

These things are all good.

And they are all things that religious groups can do well. Yet I don’t think they are chiefly what type

of “community” a religious institution, offers.

This unease at including religious institutions alongside

gyms and arcades as places where people with like interests can get together

and do stuff is picked up on in another article from the Atlantic, this

one by Jake Meador, editor-in-chief of Mere Orthodoxy, a millennial

generation Christian journal of religion, politics, and culture:

“The tragedy of American [houses of

worship] is that they have been so caught up in the same world [as the rest of

us] that we now find they have nothing to offer these suffering people that

can’t be more easily found somewhere else…content to function as a kind of

vaguely spiritual non-governmental organization.”

A community focused on better health, economic advancement,

or just playing chess, is a good community that will profoundly benefit its

members in many direct and indirect ways.

Yet the “community” a religious community should bring

is of a different sort.

--

It’s Okay to be Lonely, If…

Meador goes on to quote the theologian and public

intellectual (who when Time magazine voted him “America’s best theologian”

responded that, “’best’ is not a theological category”) Stanley Hauerwas, who

eloquently adds:

“Pastoral care has become obsessed

with the personal wounds of people… who have discovered their lives lack

meaning… Many of the wounds of, and aches provoked by, our current order aren’t

of a sort that can be managed or life-hacked away. They are resolved only by changing one’s

life, by becoming a radically different sort of person belong to a radically

different sort of community.”

In other words, the type of community that in the face of bigotry,

prejudice and hate, the type of community threatened to express itself in

communal prayer, the type of community that nevertheless could find in an empty

sanctuary, not a sign of defeat, but of God’s care and protection. Not a room without Jews, but with the heavenly

servants of the Divine crowding in to comfort those worshipers who dared show

up. Angels there to reassure the Jews

and answer their despairing question that echoed in the sanctuary, ayeh

makom kevodo? “Oh, where is the

place of God’s glory?” by answering them, kevodo malei olam, “the whole

Earth is full of God’s glory!”

The very same thing we imagine the angels are singing with us

when the Cantor leads us with that refrain during the Kedushah.

That is a religious community! That is the community that doesn’t just give

you something to do when you’re lonely to keep you busy – that is community

that changes loneliness. Loneliness is

an opportunity to remain a member of your community even when apart from it. To feel embraced by it even when alone. Never did I see Rabbi Schimmel disappointed

if attendance at services was a bit shvach.

He felt the enduring, eternal community of Jews all the time.

So should we! I am

still a Jew, who could be part of a minyan even if there isn’t one. I am a Jew who probably knows another Jew who

knows another Jew, who knows every other Jew in the world. I am a Jew who whether I’m dancing with a

bunch of men at an Orthodox wedding in Brooklyn, or with many hundreds of

guests at a Persian wedding in Los Angeles, or at chic and somewhat secular

American Ashkenazi wedding in a Manhattan restaurant, we’re all singing, Havah

Nagilah and praying we aren’t going to launch the groom’s head into the

chandelier when we pick him up.

That is the community we seek to create.

One that acknowledges that loneliness, like illness, like death, like

evil, cannot be eradicated but they can be fought. They can be held at bay. And most importantly, that none of them can

ever sever you from the eternal community of the Jewish People.

I pray we may be united in lifting people out from sadness to

joy and despair to hope. That we may facilitate

healing for the ill and comfort for the bereaved. And that we should always keep alive that

connection to each other we feel in our hearts today no matter where and with

who we might be in the future.

For I’ll have you know - that communal spirit, that spirit of

Am Yisrael Chai – the Jewish People Endure! That spirit each of you has

inside you today is marvelous. It is

precious. It is so special that even

God’s angels have come here to wonder at how its beauty and strength connects us

all today and always.

Shanah Tovah

No comments:

Post a Comment